Articular Cartilage Injuries

If you have further questions about articular cartilage injuries then please feel free to contact us

here.

Alternatively you can book an appointment to see us below.

Articular cartilage is the "gristle" that lines the ends of the bones in a joint. Its main role is to act as a cushion preventing joint damage. It enables the joint to move smoothly combined with the joint fluid (synovial fluid). It is a complex structure made up of different layers of cells. As a result of wear and tear or through injury, the articular cartilage can become damaged. This damage may be partial or full thickness; sometimes a piece of cartilage and bone together may become detached, a so-called osteochondral defect (OCD). This is more common in adolescents.

Joint surface damage commonly presents with pain, swelling, grating and catching. If a piece of cartilage and bone becomes detached, the knee joint may lock (become stuck).

Mr. Barnett will ask you a series of questions and will then perform a physical examination of the knee. X-rays will need to be performed and very often an MRI scan will be undertaken to look at the knee in more detail and confirm the diagnosis.

These defects do not heal, however using arthroscopy (keyhole surgery) any rough edges of articular cartilage can be smoothed off and made stable using a technique called chondroplasty. Any loose pieces of cartilage debris can be washed out of the joint also. If this partial thickness defect follows a traumatic injury, then the prognosis is good following surgery; if the defect is part of an arthritic process within the knee, the result is less predictable and benefit may be short-lived.

This implies there is a hole or divot in the articular cartilage down to bone. Treatment requires that the hole be filled in. There are 2 commonly performed procedures which deal with this:

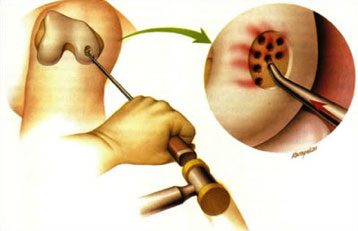

Figure 1: picture showing perforations made in the bone during microfracture

This can be performed as part of a routine arthroscopy. It is a cheap and successful way of managing localised full-thickness defects. A sharp probe is used to make a series of perforations several millimetres deep into the bone (see fig. 1).

This causes the bone to bleed which liberates lots of growth factors which encourage a new type of cartilage (fibrocartilage) to form. In approximately 80% of patients, this layer will successfully integrate with the surrounding normal articular cartilage. This is first-line treatment for isolated full thickness defects. It is not an appropriate treatment for generalised arthritis. Following microfracture, you will need to use crutches and your weight bearing may be restricted for up to 6 weeks.

Figure 2: photograph illustrating injection of cartilage cells underneath a membrane which has been stitched to the surrounding articular cartilage

This technique involves 2 separate operations. The first operation is undertaken using key-hole surgery and involves taking a small piece of healthy articular cartilage from your knee joint. This is removed and sent to a laboratory where the cartilage is used for cell culture to make millions of new cartilage cells. When enough cartilage cells have been made, a second operation is performed to re-implant them into the knee. A larger incision is made over the knee this time and the cells are implanted either under a membrane (ACI) (see fig 2) or within a matrix (MACI) which is carefully stitched to the surrounding articular cartilage.

These may be suitable for reattachment or internal fixation of the fragment (see fig. 3). This can be done either using keyhole surgery or through a larger incision. The best results are achieved if the fragment is still partially attached or if the problem has arisen very recently. Occasionally, it may not be possible to reattach the fragment and in this case microfracture or autologous chondrocyte implantation procedures (see above) may be required in the future to treat the problem.